(Some images will zoom – Left click to zoom in, use browser return arrow to go back)

Our Scottish trip had got off to a great start with bright sun and settled conditions most of the time, especially on Skye (see posts #223, #224, #225 and #226), but it was time to move on while the weather was still holding. Chris and I have used Torridon as a stopover in the past, and it’s a short, convenient drive from Skye, so Torridon it was!

Border Collie ‘Mist’ has a very good internal clock, and she soon works out when it’s time for a walk (the same clock seems to work quite well for dinner time as well), and on the morning after we arrived at Torridon she was raring to go. I had planned a walk out to Coire Mhic Fhearchair, one of the most dramatic corries in Scotland – there were no mountain summits on the trip, which didn’t bother Chris in the slightest, but a there was a promise of outstanding mountain scenery.

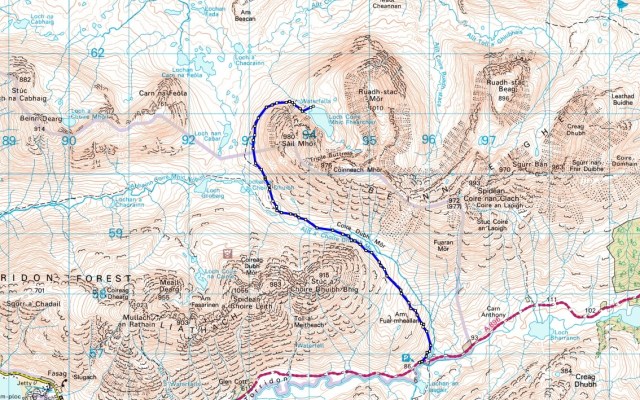

The route was on a good track running between the two mountain masses of Beinn Eighe and Liathach. The plan was to walk the track to the corrie and to return the same way, a total of almost 14 kms (about 8¾) miles with a height gain of 575 metres (almost 1900 feet). The northeast side of Liathach was a constant companion for much of the way, but eventually we parted company to head round the shoulder of Sail Mhor.

The route so far had been a gently rising path, but we had to gain altitude eventually – when the time came it was pretty short lived, with a height gain of 100 metres over 500 metres of horizontal travel. The reward for this fairly minimal effort was one of the best spots for a picnic that you could wish for.

The corrie is a big amphitheatre surrounded on three sides by the mountains of Sail Mhor, Coinneach Mhor and Ruadh stac Mhor. In the centre of the corrie lies the peaceful lake of Loch Coire Mhic Fhearchair, but the most striking feature is the huge mass of ‘Triple Buttress’ with its three rock walls rising about 300 metres in height and it’s hard to imagine a more impressive setting. It hasn’t always been as peaceful though – in March 1951, Triple Buttress was the setting for a tragic air-crash which, it would turn out, was to have far-reaching consequences.

* * * * *

On the evening of 13 March 1951, an Avro Lancaster aircraft took off from RAF Kinloss on the Moray Firth for a navigation exercise in the Rockall and Faroes area. The weather was atrocious with strong winds from the northeast. The last radio message from the aircraft had given their position as 60 miles north of Cape Wrath – from there they should have headed southeast towards Kinloss, but the strong side-wind was pushing them towards the mountains of Torridon. The aircraft did not return to base, and was listed as missing.

For two days, other aircraft from RAF Kinloss flew search missions, but without more accurate information it was a hopeless task. The first clue came two days later from a twelve-year-old boy living at Torridon who remembered seeing a red glow in the sky near to Beinn Eighe – another search mission was flown, this time to the Torridon area, and the missing Lancaster was located just below the summit of Coinneach Mhor, directly above Triple Buttress. Another 5 metres (16 feet) of altitude and the Lancaster might have cleared the summit.

Prior to WW2 there were no mountain rescue teams in the UK – in the case of a mountain accident a rescue party would be formed from climbers and mountaineers in the local area, sometimes assisted by local police officers, shepherds, quarrymen or gamekeepers. During the war, there was a substantial rise in the number of flying accidents due to the increased training activity, which led to the Royal Air Force forming unofficial Search And Rescue teams in North Wales, the Lake District and Scotland.

It soon became apparent that this ad hoc arrangement was not satisfactory, and in 1943 the first dedicated RAF MRT (Mountain Rescue Team) came into being at RAF Llandwrog near Caernarfon under Flt/Lt George Graham. By the end of WW2 there were nine official RAF MRT’s, but a lower incidence of flying accidents resulted in a reduction in the number of teams. At the time of the Beinn Eighe accident, the nearest RAF MRT was based at RAF Kinloss, the home base of the crashed Lancaster.

On 11 March, two days before the Lancaster was declared missing, the RAF Kinloss team had been asked to assist in the recovery of the body of a climber killed in a climbing accident in the Cairngorms (by this time, the RAF was being called to assist with civilian incidents on a regular basis). The operation had been a drawn out, arduous task and almost as soon the Team returned to RAF Kinloss they were put on standby to search for the missing aircraft. On 17 March, following the discovery of the crash site by the search aircraft, the Kinloss team made the first attempt to reach the Lancaster.

Over the next three days, the RAF Kinloss team made several attempts to reach the crash site. One early attempt was made even more difficult when a local police officer advised that the best approach was from the north from Bridge of Grudie. The Team then changed tactics, following the same route that Chris and I took on our walk. Although this gave an easier approach, the airmen were hampered by appalling weather and difficult mountain conditions.

They were also hampered by lack of suitable equipment and training. In his book ‘Whensoever’, an excellent history of the RAF Mountain Rescue Service, ex RAF Edzell MRT member Frank Card describes the situation – “Only the enthusiastic mountaineers … had good gear, and that was because they bought it. Ice-axes were unheard of at Edzell. Kinloss had six or so but a report after this incident said that nobody knew how to use them”.

After several unsuccessful attempts to reach the main wreck above Triple Buttress, the Team was withdrawn on 20 March. The Moray Mountaineering Club offered assistance, but this was turned down by the RAF. The first successful attempt to reach the site at the top of the buttress was by Royal Marine Commando, Captain Mike Banks and his Royal Navy climbing partner, Angus Erskine. Banks and Erskine were experienced and accomplished mountaineers, but they found conditions on the mountain to be near their own personal limits.

It was 30 March before the first body was recovered. This must have been a harrowing operation for the MRT members – the aircraft was from the same base, and some team members would have known the crew, either socially or on the flight line at Kinloss. The recovery operation continued over the following weeks, but the task continued to be hampered by deep snow and appalling weather – the last body of the crew of eight was finally recovered on 27 August.

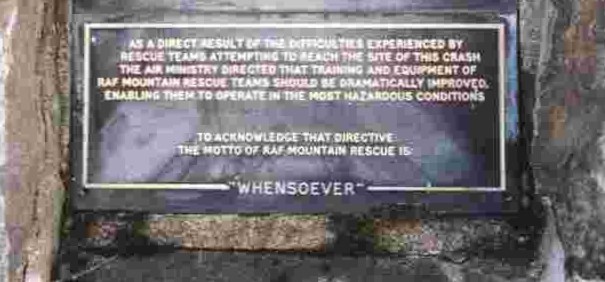

I mentioned above that there were far reaching consequences as a result of the Beinn Eighe crash. The RAF MRT’s had been under-resourced since WW2, and an enquiry after the crash voiced criticism, but a further problem was conscription – a man would join the RAF and become a rescue volunteer, but by the time he was trained and experienced, it was time to return to civilian life. After Beinn Eighe the Air Ministry might have abandoned mountain rescue altogether, but instead went in the opposite direction.

The following year saw the first organised summer and winter climbing training in RAF MR under Sergeant (later Flight Sergeant) Johnnie Lees. Lees was an RAF Physical Training Instructor, but more importantly he was already an experienced and skilful climber and mountaineer, both in the UK and the Alps. Over the next decade, Lees and others brought the RAF teams to the high standard that they still hold today, and the RAF Mountain Rescue Service remains one of the finest Search And Rescue organisations in the world.

* * * * *

The majority of civilian mountain rescue teams in the UK were formed in the 1950’s through to the 1970’s, and the RAF teams provided much of the inspiration and experience in the early days. Civilian teams still use military radio voice procedure, and in North Wales some of the teams have even adopted the RAF Valley term ‘troops’ for their members. Flt/Lt George Graham provided the original inspiration at RAF Llandwrog, but the enquiry after the Beinn Eighe crash pointed the RAF teams towards greater excellence, and this ultimately had a knock-on effect on civilian mountain rescue in the UK.

When I was in my teens I came across the book ‘Two Star Red’ by Gwen Moffat, which was the story of the early days of RAF MR. I was in the Air Cadets at the time and had also just started walking the local hills back home. The book was inspiring and it started me on a life of adventure in climbing and mountaineering – I’ve still got my copy, though sadly it’s now out of print. Eventually it led me to mountain rescue as a team member – in the 1980’s and 90’s I was a member of Penrith MRT and I’m now a member of NEWSAR (North East Wales Search And Rescue).

* * * * *

When Chris and I took our walk up to Coire Mhic Fhearchair, I already had a real sense of the history of the place. I knew the story from ‘Two Star Red’ and in a way it was a pilgrimage to the memory of those who died in the crash and to the fortitude and endurance of the men who brought them down from the mountain.

For a hungry Border Collie it was time for dinner, but on the way back down I was thinking of ways to fit in an extra day to go up to Beinn Eighe summit – a week later I was back.

Text and images © Paul Shorrock except where stated otherwise.

p.s. I’ve had to edit the story of the Beinn Eighe operation because of the length of the tale. ‘Two Star Red’ is a good start (but you will be lucky to find a copy for less than £60, usually more!) as is Frank Card’s ‘Whensoever’ mentioned above. Perhaps the best account, though, is by ex RAF team member Dave ‘Heavy’ Whalley – in his excellent blog he tells the story in three parts starting with the early part of the operation, the recovery of the first bodies and the final phase of the recovery. Go make a coffee then read on.

p.p.s. Like all civilian MR teams, NEWSAR members are volunteers, and we have to raise funds to keep the Team running – DONATIONS, however large or small, are always welcome.

It’s also worth pointing out that 95% of the members of RAF MR Teams are also volunteers, with day jobs in the RAF such as technician, fitter, etc – RAF team members give up their free time, including weekends, to train together, and our local team at RAF Valley frequently supports the six North Wales civilian teams. Long may it continue!

Fantastic walk and a wonderfully informative blog as always, much appreciated. I was hilariously confused at first as I didn’t know there are (at least) two Coire Mhic Fhearchairs, yours at Beinn Eighe then north of Kinlochewe there’s also the one I walked through on the SNT, below Sgurr Dubh and Mullach Coire Mhic Fhearchair. Yours is prettier with the lochan.

For quite a while when planning my SNT walk I was similarly fooled by there being more than one place in Scotland called Laggan! 😉 bw A

LikeLike

Haha … the confusion with names isn’t just confined to Scotland, Andrew – Wales and the Lake District also do their best to trip us up 🙂

LikeLike

Much as I’ve been up and down and around that area, I still haven’t seen the crash site! Can’t see me going up again either now unfortunately.

You should have dragged Chris up ‘the Bad Step’ for a laugh!

Carol.

LikeLike

You know this hill better than I do Carol – I need to go back and fill in some gaps. A week after Chris and I walked to the Corrie I went back with t’dog and walked the Beinn Eighe summit but not by the Bad Step and not including all the outliers – gives me a good excuse to go back to a lovely spot 😉

LikeLike

I found the Bad Step there to be one of the worst obstacles I’ve tacked in Torridon – or even in Scotland. My friend and blogger did too.

LikeLike

Pingback: #228 – The Fairy Lochs, Shieldaig near Gairloch | Paul Shorrock – One Man's Mountains AKA One Pillock's Hillocks

Pingback: #230 – The Beinn Eighe Ridge, Torridon | Paul Shorrock – One Man's Mountains AKA One Pillock's Hillocks

Pingback: #246 – Return to Beinn Eighe | Paul Shorrock – One Man's Mountains AKA One Pillock's Hillocks

Pingback: #330 – Behind Liathach | Paul Shorrock – One Man's Mountains AKA One Pillock's Hillocks